C++ GAME AUDIO ENGINE PART 1 - MULTITHREADED ARCHITECTURE

This is the first in a short series of posts about designing a C++ audio engine, and I want to discuss overall architecture as well as the mechanics of multithreading in a real-time environment. (Especially one where you could potentially blow out someone’s speakers!)

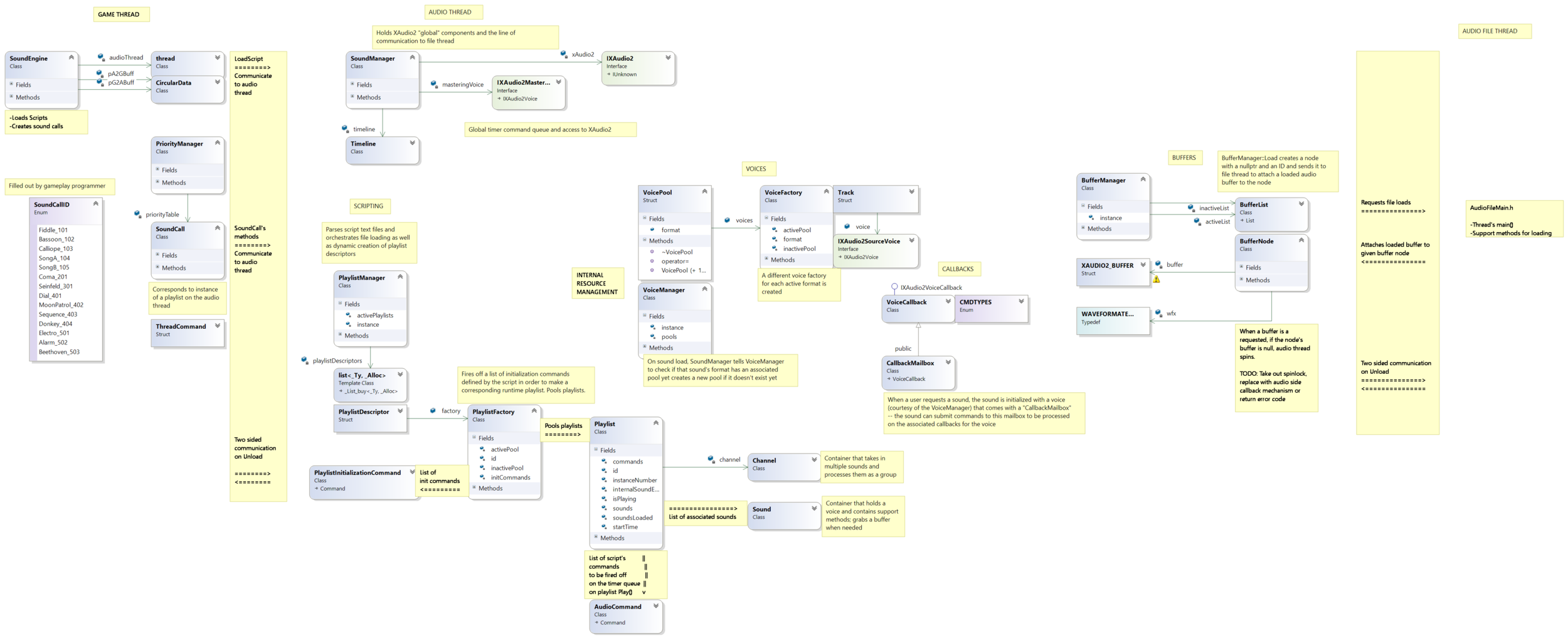

In the interest of jumping right into the deep end, here is a class diagram of my “Flim Audio Engine” from college. The thread boundaries are the part we are going to focus on here.

There is a lot of gunk that goes on internally to make a game programmer feel like a superhero, and clearly most of the workload of the engine is on the audio thread. The communication between threads is an important issue that should be addressed early, since it affects the overall layout of your engine and allows you to add more complex calculations down the road such as convolution and FFTs without worry about lowering the FPS of the game.

How To Start Up A std::thread

There are many ways to skin this cat, so before talking about the architecture of the engine I want to go over my approach to configuring threads in this scenario. I like it because the locking is very contained; we will be using a special ring buffer whose pop and push methods have mutex locks around the data reads and writes of command objects, so each thread can safely submit commands and read commands knowing the data won’t become compromised. For example, here is the pop of a ring buffer, used to check for command reads:

errcode RingBuffer::CheckForCommands(ThreadCommand &command)

{

// here is the locking

this->mtx.lock();

errcode err = errcode::COMMAND_AVAILABLE;

if (head == tail && !full) // your buffer is empty

{

err = errcode::NO_MORE_COMMANDS;

}

else // got to chase your tail!

{

// read the command

command = this->commandArray[head.index()];

head++;

this->full = false;

// if the tail and head are no longer chasing

// one another, your ring buffer is all empty!

this->empty = (head == tail);

}

// then you unlock

this->mtx.unlock();

return err;

}The other necessary lock I found in this approach is on termination: when your game thread is ending, you send a termination command over to the audio thread and then spin in a while loop until the audio thread writes back with a command saying it is all unloaded. There is not much else we can do in terms of coordination since in this approach we detach all threads on creation and technically have no clean control over them directly.

The last things you need to do to set up a thread are create a main() for your new parallel process and use it to initialize the STL thread.

Here is an example:

void AudioMain(RingBuffer* pIn, RingBuffer* pOut)

{

using time_ms = std::chrono::milliseconds;

// tweak this value to decide audio thread frame rate

time_ms audioThreadPeriod(1);

bool terminate = false;

while(!terminate)

{

// check for commands to deal with

ThreadCommand command

if(pIn->pop(command) == errcode::COMMAND_AVAILABLE)

{

// pick a way to process a command

command.execute();

}

std::this_thread::sleep_for(audioThreadPeriod);

}

}Then just pass your beautiful new main() to a new thread wherever you need it! The first place I’ll discuss is in the game thread’s SoundEngine class, so I’ll use an example in its constructor

SoundEngine::SoundEngine()

{

// set up ring buffers

this->GameToAudio = new RingBuffer();

this->AudioToGame = new RingBuffer();

// give your audio main() and ring buffers to a new thread

std::thread audioThread(AudioMain,

this->GameToAudio,

this->AudioToGame);

// once the thread is detached, you can only communicate

// via the ring buffers you gave it

audioThread.detach();

}DEFINING RESPONSIBILITIES

Game Side

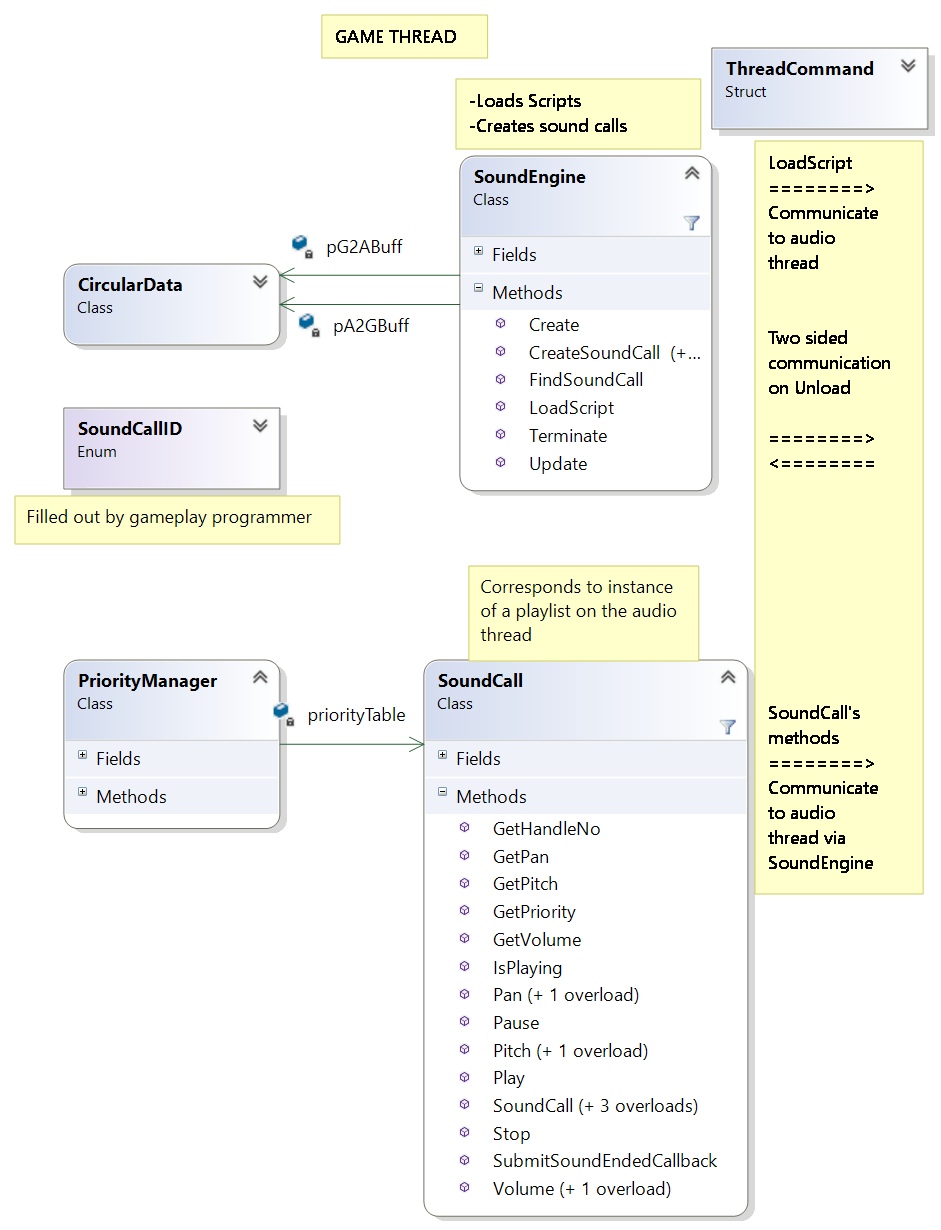

Before worrying about the nitty gritty of the audio thread, I found it helpful to start with the high-level API and start to decide which systems really should be on the game side so I could have a clear path forward when getting into internal resource management. The largest visible game thread entity should be some sort of seemingly monolithic class that the user queries for loading scripts and audio files as well as retrieving handles to audio resources at run time; I called this singleton SoundEngine. Internally, SoundEngine initializes the audio thread, facilitates communication between game and audio threads via ring buffers, and offers access for the user to request file loads, which goes to the audio thread and to the file thread under the wrapper.

Next is perhaps the most visible class to the user is the handles that the SoundEngine gives out; we will call them SoundCalls. They look and feel to the gameplay programmer like sounds themselves, and they have all the big knobs you would expect: registering callbacks, playing, pausing, panning, pitch, adding filters and reverb – but all these methods correspond to thread communications to audio object instances on the audio thread. (Those objects, Playlists, coincidentally may have a similar looking interface to the game thread SoundCalls but instead they talk directly to the audio API underneath)

Finally, I decided to keep a priority table on the game side to keep track of active sound calls and know immediately (without asking the audio thread for permission and waiting) whether a sound call should be allowed to be played or if it should kick out a currently active sound call.

Audio Side/File Side

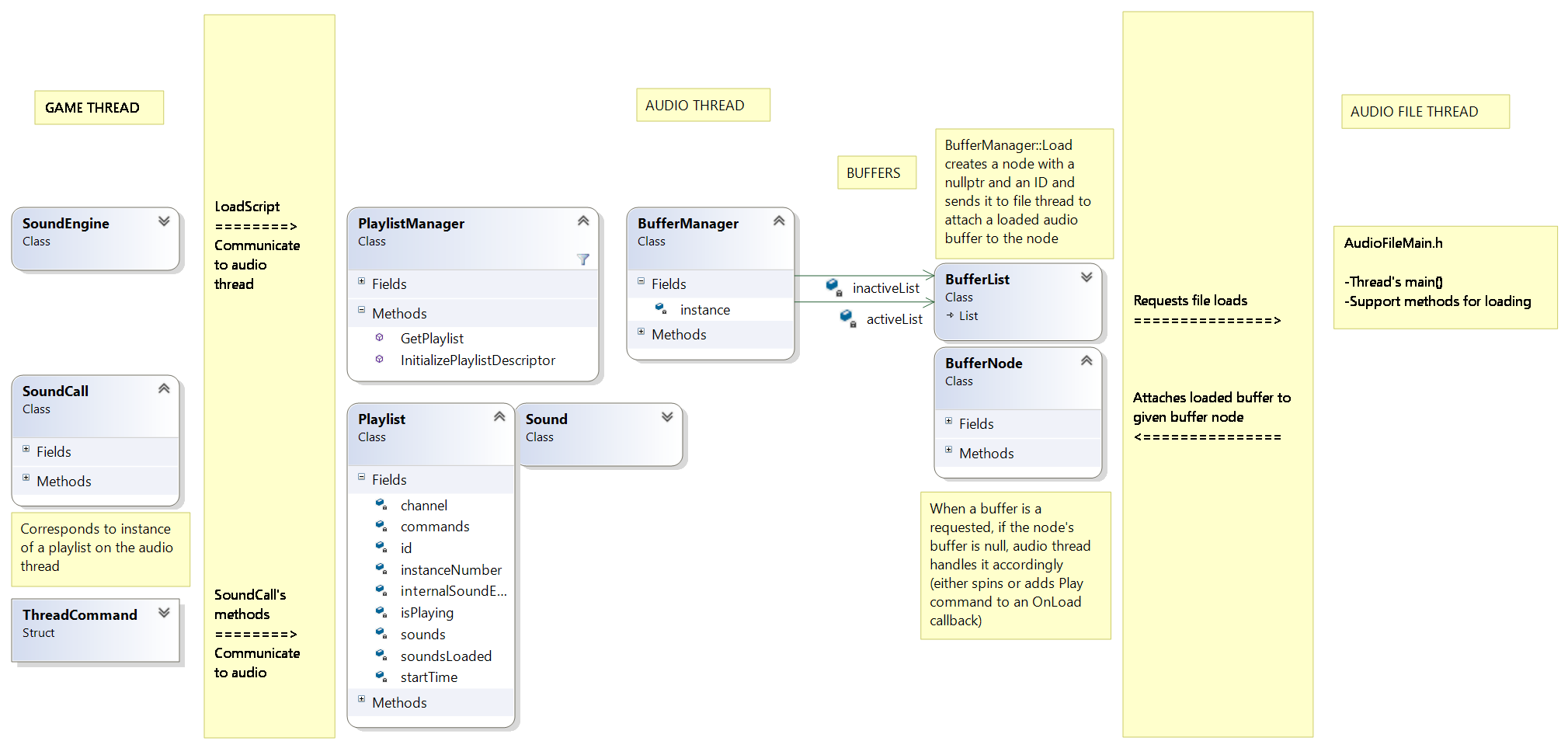

The meat of your audio engine lives (unsurprisingly) on the audio thread. The most important objects are Playlists, which are basically objects initialized with a collection of sounds and another collection of timer commands to process these sounds once the Playlist has been started (more on the timer queue later). These are what make your engine powerful, and they require some of the most complicated architecture to make them flexible and generic.

I’ll write a more in-depth post about Playlists in the future, but they are important to our discussion because they are essentially the audio side doppelgangers of SoundCalls on the game side. When a SoundCall’s Pan method is called, for example, and given a parameter of -1.0f (panned all the way to the left), a pan command is sent over the wire via the SoundEngine’s ring buffers and the associated Playlist instance pans all its associated sounds to the left.

Loading a Playlist involves the coordination of two threads; the audio thread for dealing with the coordination of audio API resource gathering and management to create a space for the playlist to live, and the file thread for the asynchronous loading of large audio files.

The signal flow for loading audio files in the above diagram goes like this:

SoundEngine makes a load command and sends it to the audio thread Playlist Manager parses the script at the given path to make a list of commands and paths to audio files In addition to requesting voices and creating audio commands for the new Playlist descriptor, the Playlist Manager asks the Buffer Manager to load each file Buffer manager makes a new node in its pool of audio files, sends a command to the file thread with a pointer to the new node and a function for a loaded callback Then the loaded state of the audio file is baked into the null state of the node’s audio file pointer. After all this, when sounds are requested on the audio side for use in Playlists, the Buffer manager finds the node associated with the appropriate audio file and checks the state of the audio file pointer. If it is a valid pointer, the sound continues and is allowed to play. If not, a Play command is added to the buffer’s OnLoaded callback and will play when the buffer has been loaded.

So far, I have not found a need for any complex architecture on the file thread itself; since its only jobs are to load audio files and attach pointers of them to buffer nodes, I have been fine with just accepting load commands on the file thread’s main loop and sending them to static support methods.

CONCLUSION

I felt this was the best way to break the ice of this post series about audio engine development, since even simple multithreading can be a bit of a mind-bending topic at times and I was able to introduce many of the larger decisions in the design of this engine via this context. In the future, I will go into detail about writing the script engine, efficiently supporting a multitude of channel configurations and sample rates in audio files, writing custom DSP effects, using encryption to avoid internal string comparisons, and more. If you have any questions or corrections, please let me know! Part 2 is about factories and pools, which are great for organizing your memory management. Thanks for reading.